28 Results

Top 10 Challenges Independent Medical Practices Face (and How to Overcome Them)

Medical Billing Software for Small Practices: Best for 2026

9 Vital Types of Medical Office Software for Your Practice

Enhanced Patient Payment Experiences Drive Revenue Growth [Infographic]

Simplifying Patient Payments [Infographic]

Generating Reports like 1,2,3

Best Reports for Billing

Speed Up Charge Entry

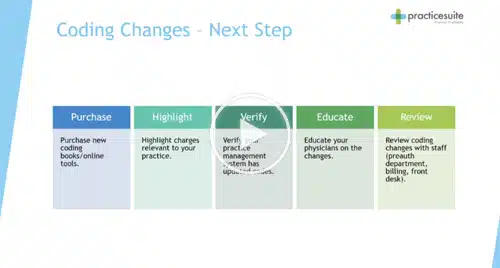

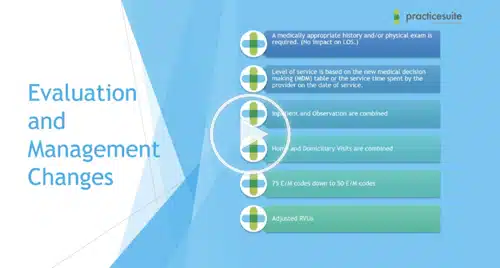

Medical Coding in 2023

Automatic ERA Posting

Getting Paid on Time

Tackling Denial Management

Streamline Your Practice Against Inflation

Innovating Care Delivery: PracticeSuite’s Digital Front Door Solutions

Optimizing Independent Medical Practices

How Far Are You Going to Protect PHI?

10+ Top EHR Software Providers for Detailed Records in 2026

10 Best Patient Appointment Scheduling Software Solutions

A Complete Guide to Medical Practice Management: 6 FAQs

Top 9 Medical Practice Management Software Features

20+ Best Medical Billing Software Solutions for 2026

Top 7 Revenue Cycle Management (RCM) Companies of 2026

AI Field Guide: What to Know Before Contract Renewal

11 Top Medical Practice Management Software Tools for 2026

Claims Denied For No Prior Authorization

Patient Engagement: More Than Portals

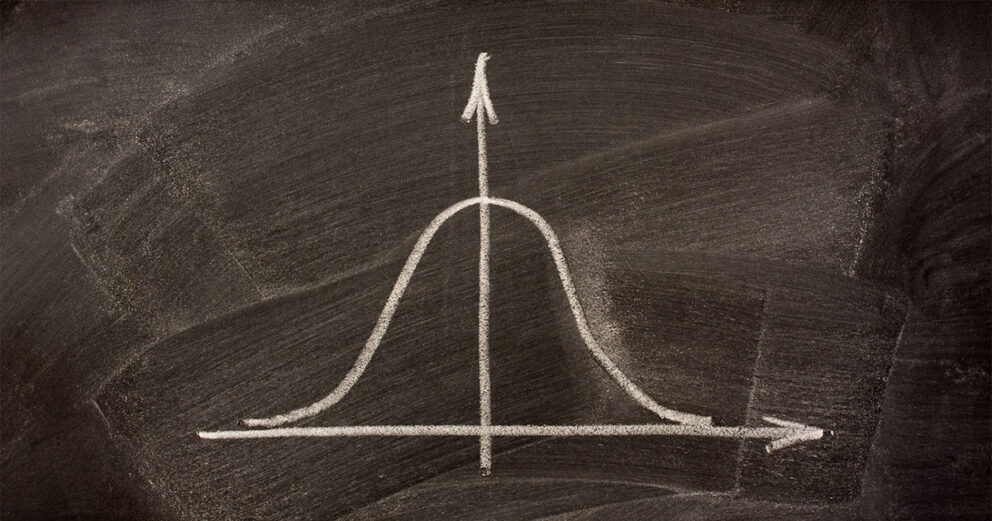

Bell Curve Module – Know Your Risk at All Times!

10 Common Medical Billing Mistakes That Cause Claim Denials – Part 1